Endangered Heritage: Amsterdam’s Canal Ring

Image Source: Unsplash

Amsterdam appears stable because its historic fabric is meticulously maintained. Yet that stability is artificial and ongoing, dependent on constant water regulation, structural monitoring, and public intervention. Unlike cities built on stone or bedrock, Amsterdam survives only as long as its environmental and urban systems are actively managed. What’s endangered here is not a single landmark, but a finely tuned system that was never designed to absorb modern climate conditions or twenty-first-century pressure.

Travel & Culture Salon proudly supports the World Monuments Fund, which has protected over 700 unique sites in 112 countries.

Below the Waterline: Quay Walls and Foundations

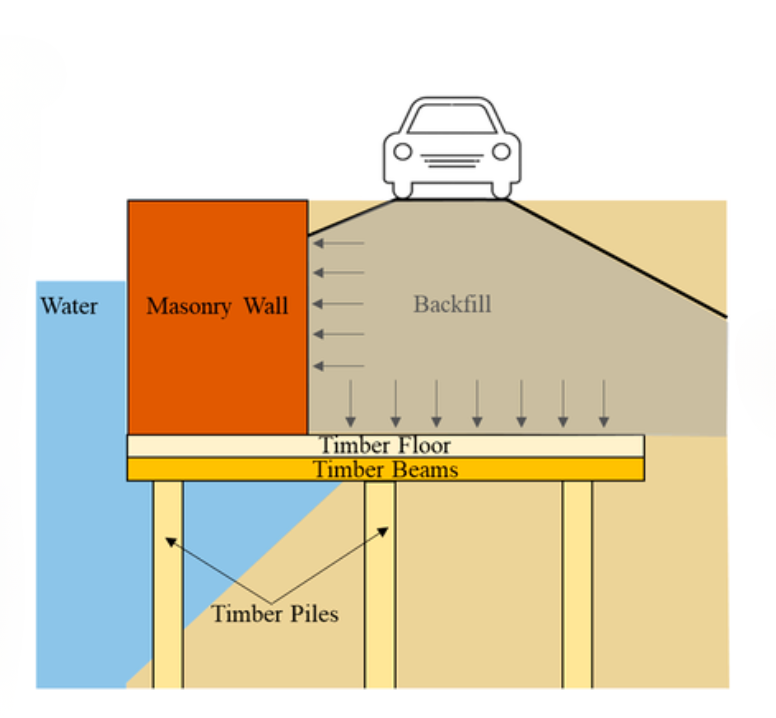

Amsterdam’s historic center is edged by canal quay walls that hold back water, support streets, and stabilize the ground along the canal edge. Many of these quays date to the 17th and 18th centuries and were built of brick masonry, often founded on timber piles, approximately 13 to 20 meters long, driven into soft, waterlogged soil to reach the firmer sand layer.

The stability of both quay walls and nearby buildings depends not on canal water levels—which are carefully managed—but on groundwater beneath the city. During extended droughts, groundwater levels drop even as canals remain full. This exposes the upper portions of wooden foundation piles to oxygen, enabling fungal decay and associated bacterial activity that weaken the wood.

As piles lose strength, the surrounding soil becomes less stable. That loss of subsurface support increases pressure on adjacent quay walls, causing them to tilt, crack, or bulge toward the canal. Approximately 100 quay sections (approximately 17 kilometers) are now considered at high risk of failure, and entire streets in the historic center are under continuous monitoring for movement and subsidence.

The Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal with the Flower Market, 1686, Gerrit Berckheyde, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid

The consequences extend directly to the buildings behind the quays. Amsterdam’s historic canal houses are supported by an estimated 11 million wooden foundation piles, most dating from the 17th and 18th centuries. According to the City of Amsterdam, roughly one quarter of all buildings now show foundation damage or are considered at risk, with repairs frequently exceeding €100,000 per property. Because canal houses sit only meters from the canal edge, instability in the quay wall can quickly translate into foundation failure across entire rows of historic buildings.

This is not a theoretical risk. Groundwater loss, biological decay, and structural instability now form one of the most widespread and costly threats to Amsterdam’s historic fabric.

The Canal Ring as Infrastructure, Not Scenery

The seventeenth-century canal belt—Grachtengordel—was engineered as a functional urban system. Canals managed transport and drainage; quay walls supported loading and unloading; bridges ensured circulation through a dense commercial city. This was working infrastructure, not decorative scenery.

Crucially, the system was designed for the loads of its time. Bridges and quay walls were calibrated to carry carts and horses, not modern traffic, mechanical vibration, or the constant passage of heavy tour boats. Many of these structures still rely on masonry and timber substructures that predate modern engineering standards, leaving them especially sensitive to vibration and concentrated loads.

Today, the canal ring absorbs levels of use its designers could never have anticipated. Amsterdam receives more than 20 million visitors annually, while fewer than one million people live in the city. The physical consequences are increasingly visible. Quay wall failures along canals, such as the Singel and Kloveniersburgwal, have necessitated emergency stabilization and long-term reconstruction, often carried out incrementally to avoid destabilizing adjacent historic buildings.

“Amsterdam faces urgent challenges such as the energy transition, infrastructure modernisation, and urban greening. Quay walls can play a crucial role in these transitions. Where maintenance and renovation were once seen as purely technical, the Multifunctional Quay Walls project demonstrates how these activities can contribute to a future-proof city. Imagine quay walls that are strong and durable but also accommodate greenery, aquathermal energy, and circularity.”

Much of what now appears as “construction” along the canals is in fact large-scale reinforcement rather than new development. Aging quay walls are being stabilized or replaced section by section, frequently using steel sheet piling installed behind or in front of historic masonry to carry loads that the original structures can no longer bear. Streets are closed for extended periods, trees are removed and later replanted, and canal edges are rebuilt in phases to prevent sudden soil movement.

New construction projects—whether infrastructure upgrades or building renovations—must now operate within this reinforced landscape. Even modest work can require groundwater monitoring, vibration limits, and preemptive stabilization of nearby quay walls or foundations. As a result, construction in the historic center is increasingly shaped by the need to protect existing structures rather than to expand or transform them.

Amsterdam canal quay with modern reinforcement. Historic masonry quay walls—originally designed for carts and horses—are now supplemented with steel sheet piling and ecological planting as they struggle to support modern loads. Canal houses sit just meters from the water’s edge, meaning quay wall failure can directly threaten building foundations. Image Source: Maarten Zeehandelaar via Shutterstock Editorial License

The scale of intervention is substantial. The city has committed several billion euros over the coming decades to reinforce and replace failing quay walls throughout the historic center, while attempting to preserve the historic appearance of a system operating well beyond its original design limits.

In Amsterdam, the canal ring has not simply become historic; it has been required to function as modern infrastructure under conditions for which it was never designed.

A schematic cross-section of quays in the Netherlands, showing how vehicular traffic on the quays generates pressure distributed by the soil to the quay wall structures. Image Source: Sharma, Satyadhrik & Longo, Michele & Messali, Francesco, “A novel tier-based numerical analysis procedure for the structural assessment of masonry quay walls under traffic loads” 2023, published in Frontiers in Built Environment. Vol 9. 10.3389/fbuil.2023.1194658.

Constraints on Construction and Preservation

In Amsterdam’s historic center, construction is governed less by ambition than by constraint. Because buildings, quay walls, and foundations are structurally interdependent below ground, even modest projects can trigger far-reaching consequences.

The most visible example of these limits was the construction of the North–South metro line (Noord/Zuidlijn). Tunneling beneath the historic center caused unexpected soil movement and groundwater changes, leading to cracking and subsidence in nearby 17th- and 18th-century buildings. Some residents were forced to evacuate while the foundations were stabilized and the walls were reinforced. The project required years of monitoring, compensation, and retrofitting—at substantial cost—before it could proceed safely.

Image Source: Tsuguliev via Shutterstock

That experience reshaped how construction is approached citywide. Today, development in historic areas routinely requires layers of precaution: groundwater monitoring, strict limits on vibration and pile driving, structural surveys of neighboring buildings, and, in some cases, preemptive reinforcement before work can begin. These requirements make construction slow, technically complex, and expensive, narrowing what is feasible even before questions of design or use arise.

The consequences extend beyond engineering. Preservation increasingly involves prioritization rather than universal protection. Buildings without formal monument status—despite their age—are more likely to experience delayed intervention or incremental loss, not because they lack historical value, but because reinforcement is financially prohibitive.

Amsterdam is therefore less an exception than a case study. Its experience illustrates how heritage preservation in dense historic cities is increasingly shaped by engineering limits, cost, and long-term governance, rather than by intention alone.

The pressures facing Amsterdam’s heritage are not only structural, but demographic. In the historic center, housing has increasingly shifted toward short-term rentals and tourism-related use, while the number of full-time residents—particularly families and lower- and middle-income households—has declined.

The result is a quiet but significant transformation. Neighborhoods once shaped by daily life now cater primarily to transient populations. The historic center remains visually intact, yet its social function has changed—less a lived city than a curated environment. What ultimately survives will depend not only on engineering solutions, but on whether Amsterdam’s historic core can continue to function as a place to live, rather than only a place to visit.